IT disappeared long ago, but in 1972 the Window was still there,

peering through milky cataracts of dust, 35 feet above the floor

of Samuel Goldwyn's old Stage 7. I never would have noticed it if

Richard hadn't suddenly stopped in his tracks as we were taking

a shortcut on our way back from lunch.

"That! was when Sound!

was King!" he said, gesturing dramatically into the upper darknesses

of Stage 7.

It took me a moment,

but I finally saw what he was pointing at: something near the ceiling

that resembled the observation window of a 1930's dirigible, nosing

its way into the stage.Goldwyn Studios, where Richard

Portman and I were working on the mix of "The Godfather,"

had originally been United Artists, built for Mary Pickford when

she founded U.A. with Chaplin, Fairbanks and Griffith in the early

1920's.

By 1972, Stage 7 was

functioning as an attic stuffed with the mysterious lumbering

shapes of disused equipment but it was there that Samuel Goldwyn

produced one  of

the earliest of his many musicals: "Whoopee" (1930), starring Eddie

Cantor and choreographed by Busby Berkeley. And it was there that

Goldwyn's director of sound, Gordon Sawyer, sat at the controls

behind the Window, hands gliding across three Bakelite knobs, piloting

his Dirigible of Sound into a new world . . . a world in which Sound

was King.

of

the earliest of his many musicals: "Whoopee" (1930), starring Eddie

Cantor and choreographed by Busby Berkeley. And it was there that

Goldwyn's director of sound, Gordon Sawyer, sat at the controls

behind the Window, hands gliding across three Bakelite knobs, piloting

his Dirigible of Sound into a new world . . . a world in which Sound

was King.

Down below, Eddie Cantor

and the All-Singing, All- Dancing Goldwyn Girls had lived in terror

of the distinguished Man Behind the Window. And not just the actors:

musicians, cameramen (Gregg Toland among them), the director, the

producer (Florenz Ziegfeld) even Sam Goldwyn himself. No one could

contradict it if Mr. Sawyer, dissatisfied with the quality of the

sound, leaned into his microphone and pronounced dispassionately

but irrevocably the word "Cut!"

By 1972, 45 years after

his exhilarating coronation, King Sound seemed to be living in considerably

reduced circumstances. No longer did the Man Behind the Window survey

the scene from on high. Instead the sound recordist was usually

stuck in some dark corner with his equipment cart. The very idea

of his demanding "Cut!" was inconceivable: not only did none of

them on the set fear his opinion, they hardly consulted him and

were frequently impatient when he did voice an opinion. Forty-five

years seemed to have turned him from king to footman.

Was Richard's nostalgia

misplaced? What had befallen the Window? And were sound's misfortunes

all they appeared to be?

There is something about

the liquidity and all-encompassing embrace of sound that might make

it more accurate to speak of her as a queen rather than a king.

But was she then perhaps a queen for whom the crown was a burden,

and who preferred to slip on a handmaiden's bonnet and scurry incognito

through the back passageways of the palace, accomplishing her tasks

anonymously?

There is a similar mystery

hidden in our own biology: four and a half months after we are conceived,

we are already beginning to hear. It is the first of our senses

to be switched on, and for the next four and a half months sound

reigns as a solitary Queen of the Senses. The close and liquid world

of the womb makes sight and smell impossible, taste and touch a

dim and generalized hint of what is to come. Instead, we luxuriate

in a continuous bath of sounds: the song of our mother's voice,

the swash of her breathing, the piping of her intestines, the timpani

of her heart.

Birth, however, brings

with it the sudden and simultaneous ignition of the other four senses,

and an intense jostling for the throne that Sound had claimed as

hers alone. The most notable pretender is the darting and insistent

Sight, who blithely dubs himself King and ascends the throne as

if it had been standing vacant, waiting for him.

Surprisingly, Sound

pulls a veil of oblivion across her reign and withdraws into the

shadows.

So we all begin as hearing

beings our four and a half month baptism in a sea of sound must

have a profound and everlasting effect on us but from the moment

of birth onward, hearing seems to recede into the background of

our consciousness and function more as an accompaniment to what

we see. Why this should be, rather than the reverse, is a mystery:

why does not the first of our senses to be activated retain a lifelong

dominance of all the others?

Something of this same

situation marks the relationship between what we see and hear in

the cinema. Film sound is rarely appreciated for itself alone but

functions largely as an enhancement of the visuals: by means of

some mysterious perceptual alchemy, whatever virtues sound brings

to film are largely perceived and appreciated by the audience in

visual terms. The better the sound, the better the image.

What in fact had given

film sound its brief reign over the film image was a temporary and

uncharacteristic inflexibility. In those first few years after the

commercialization of film sound, in 1926, everything had to be recorded

simultaneously music, dialogue, sound effects and once recorded,

nothing could be changed. The old Mel Brooks joke about panning

the camera to the left and revealing the orchestra in the middle

of the desert was not far from the truth.

Clem

Portman (Richard's father), Gordon Sawyer, Murray Spivack and the

other founding fathers of film sound had the responsibility for

recording Eddie Cantor's voice, and the orchestra accompanying him,

and his tap dancing all at the same time, in as good a balance as

they could manage. There was no possibility of fixing it later in

the mix, because this was the mix. And there was no possibility

of cutting out the bad bits, because there was no way to cut what

was being chiseled into the whirling acetate of the Vitaphone discs.

It had to be right the first time, or you called "Cut!" and began

again.

Clem

Portman (Richard's father), Gordon Sawyer, Murray Spivack and the

other founding fathers of film sound had the responsibility for

recording Eddie Cantor's voice, and the orchestra accompanying him,

and his tap dancing all at the same time, in as good a balance as

they could manage. There was no possibility of fixing it later in

the mix, because this was the mix. And there was no possibility

of cutting out the bad bits, because there was no way to cut what

was being chiseled into the whirling acetate of the Vitaphone discs.

It had to be right the first time, or you called "Cut!" and began

again.

POWER on a film tends

to gravitate toward those who control a bottleneck of some kind.

Stars wield this kind of power, extras do not; the director of photography

usually has more of it than the production designer. Film sound

in its first few years was one of these bottlenecks, and so the

Man Behind the Window held sway, temporarily, with a kingly power

he has never had since.

The true nature of sound,

though its feminine fluidity and malleability was not revealed

until the perfection of the sprocketed 35-millimeter optical sound

track (1929), which could be edited, rearranged and put in different

synchronous relationships with the image, opening up the bottleneck

created by the inflexible Vitaphone process. This opening was further

enlarged by the discovery of re-recording (1929-30), where several

tracks of sound could be separately controlled and then recombined.

These

developments took some time to work their way into the creative

bloodstream as late as 1936, films were being produced that added

only 17 additional sound effects for the whole film (instead of

the many thousands that we have today). But the possibilities were

richly indicated by the imaginative sound work in Disney's animated

film "Steamboat

Willie" (1928) and de Mille's live-action prison film

"Dynamite" (1929). Certainly they were well established by the time

of Spivack and Portman's ground-breaking work on "King Kong" (1933).

These

developments took some time to work their way into the creative

bloodstream as late as 1936, films were being produced that added

only 17 additional sound effects for the whole film (instead of

the many thousands that we have today). But the possibilities were

richly indicated by the imaginative sound work in Disney's animated

film "Steamboat

Willie" (1928) and de Mille's live-action prison film

"Dynamite" (1929). Certainly they were well established by the time

of Spivack and Portman's ground-breaking work on "King Kong" (1933).

In

fact, animation of both the "Steamboat Willie" and the "King Kong"

varieties has probably played a more significant role in the evolution

of creative sound than has been acknowledged. In the beginning of

the sound era, it was so astonishing to hear people speak and move

and sing and shoot one another in sync that almost any sound was

more than acceptable. But with animated characters this did not

work: they are two-dimensional creatures who make no sound at all

unless the illusion is created through sound out of context: sound

from one reality transposed onto another. The most famous of these

is the thin falsetto that Walt Disney himself gave to Mickey Mouse,

but a close second is the roar that Murray Spivack provided King

Kong.

In

fact, animation of both the "Steamboat Willie" and the "King Kong"

varieties has probably played a more significant role in the evolution

of creative sound than has been acknowledged. In the beginning of

the sound era, it was so astonishing to hear people speak and move

and sing and shoot one another in sync that almost any sound was

more than acceptable. But with animated characters this did not

work: they are two-dimensional creatures who make no sound at all

unless the illusion is created through sound out of context: sound

from one reality transposed onto another. The most famous of these

is the thin falsetto that Walt Disney himself gave to Mickey Mouse,

but a close second is the roar that Murray Spivack provided King

Kong.

There is a symbiotic

relationship between the techniques that we use to represent the

world and the vision that we attempt to represent with those same

techniques: a change in one inevitably results in a change in the

other. The sudden availability of cheap pigments in flexible metal

tubes in the mid-19th century, for instance, allowed the Impressionists

to paint quickly out of doors in fleeting light. And face to face

with nature, they realized that shadows come in many other colors

than shades of gray, which is what the paintings of the previous

"indoor" generations had taught us to see.

Similarly, humble sounds

had always been considered the inevitable (and therefore mostly

ignored) accompaniment of the visual stuck like an insubstantial,

submissive shadow to the object that "caused" them. And like a shadow,

they appeared to be completely explained by reference to the objects

that gave them birth: a metallic clang was always "cast" by the

hammer, just as the village steeple cast its shape upon the ground.

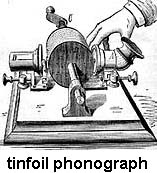

Prior

to Edison's astonishing invention of the phonograph in 1877, it

was impossible to imagine that sound could be captured and played

back later. In fact, sound was often given as the prime example

of the impermanent: a rose that wilted and died as soon as it bloomed.

Prior

to Edison's astonishing invention of the phonograph in 1877, it

was impossible to imagine that sound could be captured and played

back later. In fact, sound was often given as the prime example

of the impermanent: a rose that wilted and died as soon as it bloomed.

Magically, Edison's

discovery loosened the bonds of causality and lifted the shadow

away from the object, standing it on its own and giving it a miraculous

and sometimes frightening autonomy. According to an account in "Ota

Benga," a 1992 book by P. V. Bradford, King Ndombe of the Congo

consented to have his voice recorded in 1904 but immediately regretted

it when the cylinder was played back: the "shadow" danced on its

own, and he heard his people cry in dismay: "The King sits still,

his lips are sealed, while the white man forces his soul to sing!"

The optical film soundtrack

was the equivalent of pigment in a tube, and sound's fluidity the

Impressionist's colored shadow.

Neither Richard Portman

nor I had any inkling, on that afternoon when he showed me the Window,

that the record-breaking success of "The Godfather" several months

later would trigger a revival in the fortunes of the film industry

in general and of sound in particular.

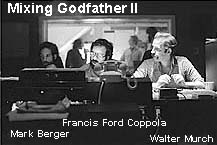

Three

years earlier, in 1969, I had been hired to create the sound effects

for, and mix, "The Rain People," a film written, directed, and produced

by Francis Ford Coppola. He was a recent film school graduate, as

was I, and we were both eager to make films professionally the way

we had made them at school. Francis had felt that the sound on his

previous film ("Finian's Rainbow") had bogged down in the bureaucratic

and technical inertia at the studios, and he didn't want to repeat

the experience.

Three

years earlier, in 1969, I had been hired to create the sound effects

for, and mix, "The Rain People," a film written, directed, and produced

by Francis Ford Coppola. He was a recent film school graduate, as

was I, and we were both eager to make films professionally the way

we had made them at school. Francis had felt that the sound on his

previous film ("Finian's Rainbow") had bogged down in the bureaucratic

and technical inertia at the studios, and he didn't want to repeat

the experience.

He also felt that if

he stayed in Los Angeles he wouldn't be able to produce the inexpensive,

independent films he had in mind. So he and a fellow film student,

George Lucas, and I, and our families, moved up to San Francisco

to start American Zoetrope. The first item on the agenda was the

mix of "The Rain People" in the unfinished basement of an old warehouse

on Folsom Street.

Ten years earlier, this

would have been unthinkable, but the invention of the transistor

had changed things technically and economically to such an extent

that it seemed natural for the 30-year-old Francis to go to Germany

and buy almost off the shelf mixing and editing equipment from

K.E.M. in Hamburg and hire me, a 26-year-old, to use them.

Technically, the equipment

was state of the art, and yet it cost a fourth of what comparable

equipment would have cost five years earlier. This halving of price

and doubling of quality is familiar to everyone now, after 30 years

of microchips, but at the time it was astonishing. The frontier

between professional and consumer electronics began to fade away.

In fact, it faded to

the extent that it now became economically and technically possible

for one person to do what several had done before, and that other

frontier between sound-effects creation and mixing also began

to disappear.

From Zoetrope's beginning,

the idea was to try to avoid the departmentalism that was sometimes

the byproduct of sound's technical complexity, and that tended too

often to set mixers, who came mostly from engineering direct descendants

of the Man Behind the Window against the people who created the

sounds. It was as if there were two directors of photography on

a film, one who lighted the scene and another who photographed it,

and neither could do much about countermanding the other.

We felt that there was

now no reason given the equipment that was becoming available

in 1968 that the person who designed the soundtrack shouldn't

also be able to mix it, and that the director would then be able

to talk to one person, the sound designer, about the sound of the

film the way he was able to talk to the production designer about

the look of the film.

At any rate, it was

against this background that the success of "The Godfather" led

directly to the green-lighting of two Zoetrope productions: George

Lucas's "American Graffiti" and Francis Coppola's "Conversation"

both with very different but equally adventuresome soundtracks,

where we were able to put our ideas to work.

Steven

Spielberg's "Jaws" soon topped the box office of "The Godfather"

and introduced the world at large to the music of John Williams.

The success of "American Graffiti" led to "Star Wars" (with music

by the same John Williams), which in turn topped "Jaws." The 70-millimeter

Dolby release format of "Star Wars" revived and reinvented magnetic

six-track sound and helped Dolby Cinema Sound obtain a crucial foothold

in film post-production and exhibition. The success of the two "Godfather"

films would allow Francis to make "Apocalypse Now," which broke

further ground in originating, at the end of the 1970's, what has

now become the standard film sound format: three channels of sound

behind the screen, left and right surrounds behind the audience,

and low-frequency enhancement.

Steven

Spielberg's "Jaws" soon topped the box office of "The Godfather"

and introduced the world at large to the music of John Williams.

The success of "American Graffiti" led to "Star Wars" (with music

by the same John Williams), which in turn topped "Jaws." The 70-millimeter

Dolby release format of "Star Wars" revived and reinvented magnetic

six-track sound and helped Dolby Cinema Sound obtain a crucial foothold

in film post-production and exhibition. The success of the two "Godfather"

films would allow Francis to make "Apocalypse Now," which broke

further ground in originating, at the end of the 1970's, what has

now become the standard film sound format: three channels of sound

behind the screen, left and right surrounds behind the audience,

and low-frequency enhancement.

Almost all of the technical

advances in sound recording, manipulation and exhibition since 1980

can be summed up in one word: digitization. The effect of digitization

on the techniques and aesthetics of film sound is worth a book in

itself, but it is enough to say at this point that it has continued

forcefully in the direction of earlier techniques to liberate the

shadow of sound and break up bottlenecks whenever they begin to

form.

The Window is long gone,

and will not now return, but the autocratic temporal power that

disappeared with it has been repaid a hundred a thousand times

in creative power: the ability to freely reassociate image and sound

in different contexts and combinations.

This reassociation

of image and sound is the fundamental pillar upon which

the creative use of sound rests, and without which it would collapse.

Sometimes it is done simply for convenience (walking on cornstarch,

for instance, happens to record as a better footstep-in-snow than

snow itself); or for necessity (the window that Gary Cooper broke

in "High Noon" was made not of real glass but of crystallized sheeted

sugar, the boulder that chased Indiana Jones was made not of real

stone but of plastic foam); or for reasons of morality (crushing

a watermelon is ethically preferable to crushing a human head).

In each case, our multi- million-year reflex of thinking of sound

as a submissive causal shadow now works in the filmmaker's favor,

and the audience is disposed to accept, within certain limits, these

new juxtapositions as the truth.

But beyond any practical

consideration, I believe this reassociation should stretch the relationship

of sound to image wherever possible. It should strive to create

a purposeful and fruitful tension between what is on the screen

and what is kindled in the mind of the audience. The danger of present-

day cinema is that it can suffocate its subjects by its very ability

to represent them: it doesn't possess the built-in escape valves

of ambiguity that painting, music, literature, radio drama and black-and-white

silent film automatically have simply by virtue of their sensory

incompleteness an incompleteness that engages the imagination

of the viewer as compensation for what is only evoked by the artist.

BY comparison, film

seems to be "all there" (it isn't, but it seems to be), and thus

the responsibility of filmmakers is to find ways within that completeness

to refrain from achieving it. To that end, the metaphoric use of

sound is one of the most fruitful, flexible and inexpensive means:

by choosing carefully what to eliminate, and then adding back sounds

that seem at first hearing to be somewhat at odds with the accompanying

image, the filmmaker can open up a perceptual vacuum into which

the mind of the audience must inevitably rush.

Every successful reassociation

is a kind of metaphor, and every metaphor is seen momentarily as

a mistake, but then suddenly as a deeper truth about the thing named

and our relationship to it. The greater the stretch between the

"thing" and the "name," the deeper the potential truth.

The tension produced

by the metaphoric distance between sound and image serves somewhat

the same purpose as the perceptual tension generated by the similar

but slightly different images sent by our two eyes to the brain.

The brain, not content with this close duality, adds its own purely

mental version of three-dimensionality to the two flat images, unifying

them into a single image with depth added.

There really is, of

course, a third dimension out there in the world: the depth we perceive

is not a hallucination. But the way we perceive it its particular

flavor is uniquely our own, unique not only to us as a species

but in its finer details unique to each of us individually. And

in that sense it is a kind of hallucination, because the brain does

not alert us to what is actually going on. Instead, the dimensionality

is fused into the image and made to seem as if it is coming from

"out there" rather than "in here."

In much the same way,

the mental effort of fusing image and sound in a film produces a

"dimensionality" that the mind projects back onto the image as if

it had come from the image in the first place. The result is that

we actually see something on the screen that exists only in our

mind and is, in its finer details, unique to each member of the

audience. We do not see and hear a film, we hear/see it.

This metaphoric distance

between the images of a film and the accompanying sounds is and

should be continuously changing and flexible, and it often takes

a fraction of a second (sometimes even several seconds) for the

brain to make the right connections. The image of a light being

turned on, for instance, accompanied by a simple click: this basic

association is fused almost instantly and produces a relatively

flat mental image.

Still fairly flat, but

a level up in dimensionality: the image of a door closing accompanied

by the right "slam" can indicate not only the material of the door

and the space around it but also the emotional state of the person

closing it. The sound for the door at the end of "The Godfather,"

for instance, needed to give the audience more than the correct

physical cues about the door; it was even more important to get

a firm, irrevocable closure that resonated with and underscored

Michael's final line: "Never ask me about my business, Kay."

That door sound was

related to a specific image, and as a result it was "fused" by the

audience fairly quickly. Sounds, however, that do not relate to

the visuals in a direct way function at an even higher level of

dimensionality, and take proportionately longer to resolve. The

rumbling and piercing metallic scream just before Michael Corleone

kills Solozzo and McCluskey in a restaurant in "The Godfather" is

not linked directly to anything seen on screen, and so the audience

is made to wonder at least momentarily, if perhaps only subconsciously,

"What is this?" The screech is from an elevated train rounding a

sharp turn, so it is presumably coming from somewhere in the neighborhood

(the scene takes place in the Bronx).

But precisely because

it is so detached from the image, the metallic scream works as a

clue to the state of Michael's mind at the moment the critical

moment before he commits his first murder and his life turns an

irrevocable corner. It is all the more effective because Michael's

face appears so calm and the sound is played so abnormally loud.

This broadening tension between what we see and what we hear is

brought to an abrupt end with the pistol shots that kill Solozzo

and McCluskey: the distance between what we see and what we hear

is suddenly collapsed at the moment that Michael's destiny is fixed.

THIS moment is mirrored

and inverted at the end of "Godfather III." Instead of a calm face

with a scream, we see a screaming face in silence. When Michael

realizes that his daughter Mary has been shot, he tries several

times to scream but no sound comes out. In fact, Al Pacino was

actually screaming, but the sound was removed in the editing. We

are dealing here with an absence of sound, yet a fertile tension

is created between what we see and what we would expect to hear,

given the image. Finally, the scream bursts through, the tension

is released, and the film and the trilogy is over.

The elevated train in

"The Godfather" was at least somewhere in the vicinity of the restaurant,

even though it could not be seen. In the opening reel of "Apocalypse

Now," the jungle sounds that fill Willard's hotel room come from

nowhere on screen or in the "neighborhood," and the only way to

resolve the great disparity between what we are seeing and hearing

is to imagine that these sounds are in Willard's mind: that his

body is in a hotel room in Saigon, but his mind is off in the jungle,

where he dreams of returning. If the audience members can be brought

to a point where they will bridge with their own imagination such

an extreme distance between picture and sound, they will be rewarded

with a correspondingly greater dimensionality of experience.

The risk, of course,

is that the conceptual thread that connects image and sound can

be stretched too far, and the dimensionality will collapse: the

moment of greatest dimension is always the moment of greatest tension.

The question remains,

in all of this, why we generally perceive the product of the fusion

of image and sound in terms of the image. Why does sound usually

enhance the image, and not the other way around? In other words,

why does King Sight still sit on his throne and Queen Sound haunt

the corridors of the palace?

In

his book "AudioVision",

Michel Chion describes an effect that he calls the acousmêtre,

which depends on delaying the fusion of sound and image to the extreme

by supplying only the sound most frequently a voice and withholding

the revelation of the sound's true source until nearly the end of

the film. Only then, when the audience has used its imagination

to the fullest, is the identity of the source revealed. The Wizard

in "The Wizard of Oz" is one of a number of examples, along with

the mother in "Psycho" and Hal in "2001" (and although he didn't

mention it, Wolfman Jack in "American Graffiti" and Colonel Kurtz

in "Apocalypse Now"). The acousmκtre is for various reasons having

to do with our perceptions a uniquely cinematic device: the disembodied

voice seems to come from everywhere and therefore to have no clearly

defined limits to its power. And yet . . .

In

his book "AudioVision",

Michel Chion describes an effect that he calls the acousmêtre,

which depends on delaying the fusion of sound and image to the extreme

by supplying only the sound most frequently a voice and withholding

the revelation of the sound's true source until nearly the end of

the film. Only then, when the audience has used its imagination

to the fullest, is the identity of the source revealed. The Wizard

in "The Wizard of Oz" is one of a number of examples, along with

the mother in "Psycho" and Hal in "2001" (and although he didn't

mention it, Wolfman Jack in "American Graffiti" and Colonel Kurtz

in "Apocalypse Now"). The acousmκtre is for various reasons having

to do with our perceptions a uniquely cinematic device: the disembodied

voice seems to come from everywhere and therefore to have no clearly

defined limits to its power. And yet . . .

And yet there is an

echo here of our earliest experience of the world: the revelation

at birth that the song that sang to us from the very dawn of our

consciousness in the womb a song that seemed to come from everywhere

and to be part of us before we had any conception of what "us" meant

that this song is the voice of another and that she is now separate

from us and we from her. We regret the loss of former unity some

say that our lives are a ceaseless quest to retrieve it and yet

we delight in seeing the face of our mother: the one is the price

to be paid for the other.

This earliest, most

powerful fusion of sound and image sets the tone for all that are

to come.