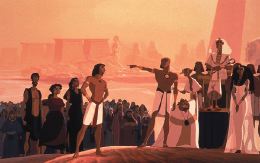

The Prince of Egypt

Using subtlety in preference to bombast, Dreamworks' biblical epic may be destined to become an animated classic. Richard Buskin talks to the audio team behind The Prince of Egypt

A

BLOOD-AND-GUTS chariot race, a massive sandstorm, a pillar offire that

reaches the sky, an exodus of more than 100,000 people, a burning bush,

the parting of the Red Sea, and no less than ten plagues were on the menu

for the sound team that toiled for up to three years on Dreamworks' recent

animated feature, The Prince of Egypt.

A

BLOOD-AND-GUTS chariot race, a massive sandstorm, a pillar offire that

reaches the sky, an exodus of more than 100,000 people, a burning bush,

the parting of the Red Sea, and no less than ten plagues were on the menu

for the sound team that toiled for up to three years on Dreamworks' recent

animated feature, The Prince of Egypt.

The directive from the studio's top brass was for the audio elements to be developed in tandem with the visuals, as the animators would be using the audio to help shape the visuals from the line-drawing phase onwards. Consequently, a far higher proportion of the sound work took place during production (as opposed to postproduction) than is the case on regular live action features.

'We pre-edit this type of film so that there's no unnecessary work done by the animators,' explains Nick Fletcher, supervising editor on The Prince of Egypt. 'The script that we start with isn't usually as tight as one on a live action movie. A lot of the people in the story department often sketch ideas and even whole sequences, pinning their drawings up on the wall and discussing everything. Then, being that we have the Avid here, it's very easy to point a video camera at those drawings and shoot them in, so that is why we now edit stuff at an earlier stage than we used to. Next we record scratch dialogue here, put music on as well as sound effects, and that is how we kind of build the story reel.

'This obviously is when ideas are very loosely developed, and the editing therefore becomes part of the process in developing the story,' he concludes. 'When people are fairly comfortable with a sequence we then bring the actors in, and we record the final production dialogue and cut that against our storyboards.'

'During the production phase my main directive was to create a fluid environment and bits of action for the transition from storyboards to animation,' adds sound designer Lon Bender who, along with Wylie Stateman, founded the Soundelux Entertainment Group back in 1982. 'The fluidness of the movement of the characters through space was totally undeveloped because they were just voices in an ADR studio and storyboards on a one-dimensional piece of paper. The movement and environment for them to act in was often created by the sound, and then the animators were able to do all of the layouts and design the movement of the characters from one location on the screen to another from the visual standpoint.'

For his part, the fact that he was so involved in the overall development of the film made Nick Fletcher feel that his job extended beyond that of picture editor. 'Whereas with live action footage you make your cuts from the daily rushes, as the editor on a film like The Prince of Egypt you can actually design shots too,' he says. 'You can say, "I'd love to get a crowd shot here", and you knock up a rough sketch and put it in, and if it works then we'll carry it through into production. We're involved in the storytelling process from the beginning, and I think that's more interesting in a way.'

Given

the high cost and time-consuming nature of animation, there is normally

not nearly as much shooting of new scenes on a feature-length cartoon

as on a live action picture, yet there were still certain shots in The

Prince of Egypt that, once viewed, required re-animating. At the same

time, while Lon Bender and Wylie Stateman (his partner at Soundelux Hollywood)

were involved from the movie's inception, several audio ideas were also

developed in the cutting room, and so there was often a close collaboration

between the Dreamworks and Soundelux teams.

Given

the high cost and time-consuming nature of animation, there is normally

not nearly as much shooting of new scenes on a feature-length cartoon

as on a live action picture, yet there were still certain shots in The

Prince of Egypt that, once viewed, required re-animating. At the same

time, while Lon Bender and Wylie Stateman (his partner at Soundelux Hollywood)

were involved from the movie's inception, several audio ideas were also

developed in the cutting room, and so there was often a close collaboration

between the Dreamworks and Soundelux teams.

A case in point is the creation of the voice of God for the pivotal scene when Moses hears from his maker via the burning bush. 'That was a particularly interesting challenge for me, and something that I was very fond of working on,' comments Nick Fletcher. 'I remember we tried so many different versions of that. Being that it had the theological aspect to it that you don't really get in most movies, some brilliant ideas just didn't work on religious grounds. For instance, in terms of the effects that we tried out to manipulate the voice, if you want to make someone sound like an alien or the Devil it's relatively easy, but of course that was a no-go for us. Idid a version myself using the actors, actresses and children within the film, kind of morphing from one voice to another, which for me was great fun to do and produced a pretty amazing sound. But it crossed the line theologically and so we had to abandon that idea.'

The task of creating God's voice was thus handed to Lon Bender and the team working at the facility of the film's music composer, Hans Zimmer. 'The challenge with that voice was to try to evolve it into something that had not been heard before,' says Bender. 'We did a lot of research into the voices that had been used for past Hollywood movies as well as for radio shows, and we were trying to create something that had never been previously heard not only from a casting standpoint but from a voice manipulation standpoint as well.'

The solution was to use the voice of actor Val Kilmer to suggest the kind of voice we hear inside our own heads in our everyday lives--as opposed to the larger than life tones with which the Creator has been endowed in prior celluloid incarnations.

The

chariot race, on the other hand, demanded a sound that realistically conveyed

the flimsy, lightweight construction of vehicles of the day. After much

experimenting, bamboo and a variety of squeaks were settled upon as the

raw elements with which the Foley artists could perform their moves.

The

chariot race, on the other hand, demanded a sound that realistically conveyed

the flimsy, lightweight construction of vehicles of the day. After much

experimenting, bamboo and a variety of squeaks were settled upon as the

raw elements with which the Foley artists could perform their moves.

'We wanted to get away from the classic Hollywood idea that, in this kind of setting, weight equals excitement,' says Lon Bender. 'We wanted something in the mid to high frequency range, not only allowing the characters to be in an environment that was real from an historic standpoint, but also enabling us to test how we could use mid to high frequency sounds that work with a score that has a lot of low and mid frequency sounds from the percussion section. In fact that was quite successful, because we weren't competing within the aural spectrum with the score, and so the chariot race not only turned out to be historically accurate, but also entirely separate from the music.'

Again frequency considerations came into play during a desert montage that highlights the changes taking place with regard to Moses' perspective on himself and the world around him, by focusing on his own diminishing stature in relation to the increasing size of his environment.

'The low frequencies expand as he gets further and further out into the desert and as the desert grows,' explains Bender. 'As we dissolve from one phase of his life to another, long exhaling breaths emphasise his new take on life, and the sound of the desert gets deeper and deeper and deeper, and finally it goes into the windstorm that completely takes over the screen. That then contrasts with the silence that follows, and the same is true with the Angel of Death sequence, which is one of my favourites.'

In this scene, which has no music, the Angel's sound comprises the breaths of adults and children, while extremely sharp knives are used to convey the Angel's movements and the souls of the deceased are represented by a single exhale.

'We purposely played everything very quiet and very subtly to add to the feeling of danger, instead of going in the traditional Hollywood direction of everything getting louder and more exciting,' says Bender. 'We went for a much more surgical sort of scariness where things are extremely quiet and lurking around in the shadows. I think that scene is very successful.'

Equally successful in its own way is the scene that depicts the parting of the Red Sea, blending the powerful visuals with huge oceanic and gale-force wind sounds that, courtesy once more of keeping a sharp ear on frequency differences, manage to circumvent Hans Zimmer's dramatic score.

'I had the elements of that score in my hands as we were putting the sounds together,' says Bender. 'There was a certain amount of clashing going on. In fact, we had to re-envision some of the big, broad sounds--mostly of the water playing against the rocks and against the sand, and where the water goes right by the camera--in order to make room for everything. These were the things that were less static, whereas the things that were static did not fly because of all of the elements of the music, which included a lot of strong woodwind instruments and also some synthesiser pads that were very heavy. These gave size and scope to it but they also conflicted with the broad organic sounds, so we went for the things that were less static and that seemed to work very well.'

Multiple systems were used on the Prince project; Pro Tools integrated with Nick Fletcher's Avid, while WaveFrame was also used for a lot of the editing.

'We

did a lot of our previews and playbacks off of the WaveFrames where we

were coming off the hard drive,' recalls Lon Bender. 'We also used the

Dolby ISDN line to play back a lot of the material off Pro Tools when

I was at a remote location in San Francisco, which is where I was most

of the time.'

'We

did a lot of our previews and playbacks off of the WaveFrames where we

were coming off the hard drive,' recalls Lon Bender. 'We also used the

Dolby ISDN line to play back a lot of the material off Pro Tools when

I was at a remote location in San Francisco, which is where I was most

of the time.'

At Soundelux, with Bender and Stateman in their complementary roles as sound designer and supervisor, the audio postproduction team consisted of two dialogue-ADR supervisors, eight sound editors, assistant sound editor, Foley supervisor, Foley mixer, a pair of Foley walkers, Foley recordist and to people taking care of any additional audio. Andy Nelson was the dialogue mixer, Anna Behlmer the effects mixer and Shawn Murphy mixed the music.

'Because there's no production track and no contamination from natural exterior recordings, you have a lot more versatility in terms of what you play and the control that you have,' says Bender, who supervised and also participated in the mix of The Prince of Egypt on Stage One at Todd-AO West. 'Animated mixes are more complex for that reason. You really have to make choices to play certain things and leave out certain things, whereas with live action you're often stuck with a production track that dictates how you play certain scenes.'

Andy Nelson spent a couple of months mixing 24 channels of dialogue on an Otari Premier console that also assigned 30 channels to the music and 64 channels to the effects. This was the first full mix that he had ever done for an animated feature, and he concurs with Bender about the advantages and drawbacks.

'It's good that you don't have to get rid of any extraneous sounds,' he says. 'The bad thing is that you've got to start creating an environment for these voices to live in, because, obviously, if you just play them the way that they're recorded straight off the microphone it's going to sound like a radio show. The thing that was interesting to me was that, right from the beginning when they discussed the style of the soundtrack and the way that we would go about the mix, it was very clear that they wanted to create a soundtrack that would be more inclined towards a live action film than a traditional animated feature. You see, it was dealing with a serious subject instead of the usual light-hearted ones that cartoons usually revolve around. In terms of the sound and the visuals you're normally creating a big illusion, but the only illusion in this film related to the characters being drawn.

'From my point of view with the dialogue, what I really strove hard to achieve was a way of creating an environment for the voices to live in, to get a sense of realistic ambience rather than just slinging a lot of echo on things and making them big and broad in the way that animated films are generally treated. I wanted to play on the subtlety of those environments, which is why the dialogue was complex. Then there were a couple of instances where it was even more complicated, such as the voice of God, where we wanted this out-of- body experience without it being booming in the traditional sense. I therefore went to great lengths to place it in the different speakers, but not in an overwhelming sense, opting instead for a warm, comfortable feeling which we achieved with the breaths that were added. That whole sequence with the voice of God and the burning bush was one of the most complicated areas, because there was this constant battle to achieve something that felt very special while not showing your hand as to how you were doing it. I think we pulled it off, but I could have spent longer on it, as we could have all spent longer on certain things.'

Needless

to say, even with a three-year schedule in which to complete the audio

production and post work, things ran down to the wire. 'There's always

a rush to make the deadline in the end, but we just do the best that we

can in the time that we have,' says Lon Bender. 'We certainly could have

taken twice as long as we did to mix the movie, and I've never worked

on a movie where that wasn't the case.'

Needless

to say, even with a three-year schedule in which to complete the audio

production and post work, things ran down to the wire. 'There's always

a rush to make the deadline in the end, but we just do the best that we

can in the time that we have,' says Lon Bender. 'We certainly could have

taken twice as long as we did to mix the movie, and I've never worked

on a movie where that wasn't the case.'

'During the three years that I was involved with The Prince of Egypt there was never a lull when we weren't doing anything,' adds Nick Fletcher, whose own work on the film lasted until just prior to it's release. 'We've got a great postproduction department at Dreamworks and the postproduction supervisor Jan Owen was guiding it through the final stages, but we'd still get into all of the print checking, signing off on the various sound formats and ensuring that everything matched.'

'We went down a lot of different roads,' comments Lon Bender. 'The soundtrack was well thought out and we tried many, many different things, some of which ended up on the screen and some of which did not. The outcome of all that we tried helped us to make decisions, and I really have to applaud Dreamworks for supporting that type of process because that's normally not done.'